[캐나다 유력신문 Globe and Mail 인터뷰에 실린 내용: “평창2018동계올림픽 한반도 단결력의 실체는?”(The unifying force of the Olympics in the Korean Peninsula)]

지난 주 인 1월 말 어느 날 오전 베이징에 아시아지부를 실치하여 보도활동 중인 GLobe and Mail아시아지부장인 Nathan VanderKlippe 및 한국인 경희대 교수인 Cynthia YOO(유소영)으로부터 한통의 전화를 받았습니다.

“서울에서 오전 KTX고속철을 타고 평창으로 넘어와 인터뷰를 하고 싶다”는 인터뷰 요청이었습니다.

평창2018 대회가 임박하여 많은 외신기자들이 한국, 특히 평창에서 활동 중이므로 외신기자 취재 협조차원에서 대변인에게도 알리고 흔쾌이 허락하였는데, 정말 바로 그날 오후 2시경에 대관령면 올림픽로에 위치한 평창2018동계올림픽 주 사무소 3층에 있는 제 사무실로 찾아 온 것입니다.

다음, 다음날 잠실 방이동 서울올림픽공원 소재 서울올림픽박물관 겸 기념관에서 평창2018동계올림픽 미국전역 방여권자(RHB: RIghts Holding Broadcaster)인 미국 NBC TV와의 현장인터뷰를 앞두고 있는 시점이라 외신에도 협조적으로 임하자는 차원에서 2시간 여 생 인터뷰에 임했습니다.

외신기자들의 특성은 인터뷰 내내 어느 한 문장도 그냥 듣고 넘기지 않는 다는 것을 과거 경험을 통해 익히 알고 있는지라 스스럼 없이 서울1988올림픽부터 평창2018 북한참가에 이르기까지 진솔한 인터뷰를 하였습니다.

심지어 명함에 쓰여진 영어 이름(Rocky Kang-Ro YOON)을 놓치지 않고 Rocky라는 영어 이름의 유래까지 물어 보았습니다.

The 63-year-old, who earned his English name with one-handed push-ups as a young man, is one of the few people who have helped organize both of South Korea's Olympics. (<사실은 만 62세인데 한 살 올려 놓았더라구요> 젊은 학창시절 한 손으로 팔 굽혀 펴기를 하게 되면서 미국 선수들이 붙여준 영어이름…)

북한선수단의 평창2018참가의 긍정적 효과를 나른 풀어 팩트 중심으로 상세히 설명하여 주었는데 인터뷰 내용에 다음과 같이 “오랜 동안 지녀온 꿈이 논란거리로 서서히 빠져들고 있는 것을 지켜보는 것으로부터 올 수 있는 비관론에 대하여 Rocky Yoon이 민감하다고 가정할 경우 그는 그 민감함을 감추는데 달인이다” (If Rocky Yoon is susceptible to the pessimism that can come from watching a long-held dream descend into controversy, he is good at hiding it.)고 묘사하면서 첫 인터뷰 글을 시작하였습니다.

평

창2018대회가 역사에 남기기를 소망하는 유산에 대한 저의 소감표현도 함께 실렸습니다:

"One day we'll tell our children, 'I was in the middle of the Olympic organizing committee, and it was a milestone for the unification of South and North Korea,'" Yoon says. (미래 언젠가 우리 아이들에게 이렇게 이야기 할 것입니다. “나는 평창2018동계올림픽조직위원회 중심부에서 근무하였는데 평창2018동계올림픽이 남북한 통일의 초석이 되었노라고 말입니다”)

평소 몇 차례 들어본 외신매체인 “Globe and Mail”에 대하여 Wiki 백과를 참조하여 보았습니다:

“캐나다에서 가장 권위있고 영향력 있는 신문이다.

이 신문의 모체는 1844년 스코틀랜드에서 이민 온 브라운이 만든 자유주의 신문 〈글로브 The Globe〉와 1872년 존 A. 맥도널드가 만든 보수주의 신문 메일 The Mail〉뒤에 〈메일 앤드 엠파이어 Mail and Empire〉로 바뀜)이라고 할 수 있다.

이 두 신문은 조지 매컬러가 〈글로브>를 인수한 1936년까지는 상호 경쟁적인 관계에 있었다. 1개월이 채 못되어 매컬러는 〈메일 앤드 엠파이어>도 사들여 둘을 합쳐 독립지인 〈글로브 앤드 메일〉을 만들었다.

〈글로브 앤드 메일>은 '독립적이지만 중립은 아닌' 입장을 지니고 있다. 이 신문은 실제로 캐나다의 민족지적인 성격을 지녔으며 담화문이나 국회에서의 논쟁 및 다른 기록들의 원문을 실음으로써 캐나다의 기록신문으로서 자리잡았다.

많은 해외특파원과 해외지부가 보내주는 외신보도는 굉장한 영향력을 갖고 있다.

1958년부터 10년이 넘도록 대부분의 미국 일간지들은 이 신문의 베이징 지부에서 보내온 중국 정보를 인용해서 기사를 써왔다 “ (출처: 위키백과)

다음은 그날 인터뷰 영어원문 Winter Olympics 2018이란 제하에 ‘한반도에서 올림픽이 내 뿜는 통합의 힘”(The unifying force of the Olympics in the Korean Peninsula)이란 소제목의 기사내용 입니다. 참고로 공유합니다:

Winter Olympics 2018

The unifying force of the Olympics in the Korean Peninsula

The Pyeongchang Winter Games have been pitched as a chance to bring harmony to the Korean Peninsula, but some worry the sporting spectacle will just offer an illusion of peace without leading to any concrete gains

The tower at the top of the Alpensia Ski Jumping Centre rises beyond a set of Olympic rings in Pyeongchang, South Korea on Feb. 2, 2018.

Charlie Riedel/AssociatedPRess

DAEGWALLYEONG, SOUTH KOREA

Published 1 day agoUp dated 1 day ago

If Rocky Yoon is susceptible to the pessimism that can come from watching a long-held dream descend into controversy, he is good at hiding it.

The 63-year-old, who earned his English name with one-handed push-ups as a young man, is one of the few people who have helped organize both of South Korea's Olympics. First came the 1988 Summer Games, which coincided with the country's grand transition to democracy. Now, the Pyeongchang Winter Games are set to land amid some of the worst tensions in modern history with North Korea, the result of its growing nuclear arsenal.

Yoon, however, is certain that the path to healing what ails the Korean Peninsula lies on the groomed slopes between the potato fields around his office in the country's remote northeast, where 2,925 of the world's top athletes will soon gather.

"One day we'll tell our children, 'I was in the middle of the Olympic organizing committee, and it was a milestone for the unification of South and North Korea,'" Yoon says. (미래 언젠가 우리 아이들에게 이렇게 이야기 할 것입니다. “나는 평창2018동계올림픽조직위원회 중심부에서 근무하였는데 평창2018동계올림픽이 남북한 통일의 초석이 되었노라고 말입니다”)

To the doubters, he has this to say: The promised peace is already under way. North Korean skiers, speed skaters, figure skaters and hockey players are already on South Korean soil, preparing to join the Olympics under a joint flag. Hundreds more are expected to follow, as officials and members of art and cheerleading troupes.

"North Korea came because of the Olympics. Otherwise they never would have dared," says Yoon, president of the International Sport Diplomacy Institute and a special adviser to the president of the Pyeongchang organizing committee.

"But we gave a good excuse to come to Korea. This is about the power of the Olympic movement: unity in diversity." (올림픽운동의 힘은 바로 다양함 속에 결속력)

The Pyeongchang Games were, in fact, intended to accomplish much more – until North Korea's involvement brought forth an undercurrent of resentment that has sapped pre-Games enthusiasm and accentuated divisions, the very inverse of the unity the country's leadership sought in its long road to the Olympics.

South and North Korean skiers participate in a joint training session at the Masik Pass ski resort in North Korea on Feb. 1, 2018.

Korea Pool/Yonhap/Associated Press

Almost two decades ago, South Korea began chasing a Winter Games as a way of cementing its place among the global elite – as a country that today makes some of the world's best cars, pop music and consumer electronics.

This will be the biggest Winter Olympics so far, with the most athletes and the most medals (and, it was revealed this week, the most condoms). Facilities construction was finished early. With a budget that is a fraction of Sochi's extravagance and a last-minute rush of corporate sponsorship, these Games might break even, too.(사상최대의 겨울올림픽으로 가장 많은 수의 참가선수와 가장 많은 메달 수<콘돔 수도 마찬가지> 모든 인프라공사 초기완공. 소치2014의 호화판 예산의 일부분 정도의 절약 예산. 막판 공기업들의 지원공세. 평창대회 균형예산대회)

"Korea is ready. Pyeongchang is ready," Yoon says. (대한민국은 분비되어 있습니다. 평창은 손님맞이 채비를 차리고 있습니다)

All that remains is to fill the world's screens with pictures of the world's best athletes carving South Korean snow and ice, the perfect rehabilitation for a national image tarnished by the menace of its next-door neighbour.

In recent years, "Korea has meant tension, a war atmosphere," says Samuel Koo, who recently served as chairman of the Presidential Council on Nation Branding. The Olympics, in contrast, can "deliver to a large segment of the population, domestically and also abroad, a message of hope and peace."

For athletes to accomplish something that has eluded nuclear negotiators would be an extraordinary victory – not only for Korean planners but for the entire Olympic movement.

Now, after waiting years for this moment – losing bids to Vancouver and Sochi before succeeding on a third attempt – South Korea has already found its coveted Olympic spotlight hijacked by a political drama whose stakes are far higher than those of the Games themselves – and whose outcome is every bit as uncertain.

In Seoul, the camera has been commandeered by the minute-by-minute spectacle of North Korea's involvement – the visits and the meetings, the beauty of the cheerleaders who will be dispatched to the south, the twists and turns of planned and cancelled events.

At least, Games supporters can boast, the Pyeongchang Olympics have brought the moment of peaceable unity promised by President Moon Jae-in. On Jan. 9, North and South Korean representatives met for their first formal talks in two years, a smiling event that brought promises of the two countries participating in the opening ceremony under a common flag, forming a joint women's hockey team and opening lines of communication for further discussion.

The Gangneung Hockey Centre at the Olympic Park in Gangneung, South Korea will host the men’s hockey tournament and the women’s hockey gold medal match.

Associated Press

"It is entirely due to the Games" that the two sides could "sit face to face," Moon said in late January. "Such dialogue came while the possibility of war again loomed."

A joint presence could even serve as "missile insurance against attacks during the Olympics," said Jules Boykoff, a scholar on the politics of sports who has written extensively about the Games.

"It can do no harm – and possibly some good," said Dick Pound, the long-time International Olympic Committee member who wrote a book about the Seoul Games in 1988.

Among the South Korean public, too, the Olympics as a force for peace has been appealing, with two-thirds in favour of the idea in a Korea Press Foundation survey released this week.

"I don't believe the nuclear problem will be solved through the Olympics. But when there's an opportunity for peace, it's important to do our work to keep opening the doors," Do Jongwhan, Minister of Culture, Sports and Tourism, said in an interview.

The Games, he says, will leave a "legacy of peace."

The bullet train from Seoul station accelerates to 250 kilometres an hour as it flies east toward Gangwon province, a place of granite peaks and sandy beaches lined with pine trees that tourists, who come by the tens of millions, call a "fairy tale land." Gangwon is home to the country's third-tallest mountain, one of Asia's largest limestone caves – and, for much of its modern history, the kind of bleak economic outlook that causes local children to flee life on the leek and radish fields.

"We've always felt isolated, left out," said Kim Jin-sun, who became the provincial governor in 1998. Elected in the midst of the Asian financial crisis then ravaging the country, he was determined to re-invigorate his home. The mountains limited the region's options for economic development. So why not use them to his advantage?

South Korea's first modern ski resort opened in Gangwon in 1975, and Kim saw a way to thrust his region onto the world stage: He would bring home an Olympics.

South Korean skiers on a chartered flight wave to the media before taking off to North Korea at Yangyang International Airport in Yangyang, South Korea.

Associated Press

"It was a chance for Korea to move up to another level in every manner possible – socially, economically, you name it," he said.

He just had to convince the International Olympic Committee.

But he had what he thought was a potent argument. The Korean War split Gangwon. Today, it's the only province where north and south retain the same name – cut in half by the military demarcation line. "We are really the symbol of division in the country," Kim said.

Give Pyeongchang the Olympics, he said as far back as 2003, and the IOC "can make a great contribution to mankind."

Kim himself set out to make that happen. He believes he was the first South Korean provincial governor to travel to Pyongyang on an official visit. Over three leadership terms, his North Korea outreach included a memorandum of understanding toward a joint Olympic team and agreements to co-train athletes and co-operate on cultural performances in a united opening ceremony. He researched potential sites for Olympic events in North Korea's Gangwon, discovering the remnants of ski slopes from the Japanese colonial period. Those wouldn't work, he figured, but perhaps Pyongyang's pyramid-shaped ice rink could be a hockey venue.

He even sounded out a possible name: the "Pyeonghwa," or "Peace" Olympics.

"The leadership that started the bidding in 2003 envisioned the Pyeongchang Winter Olympic Games as a stage in the peaceful unification of the two Koreas," said Moon Dae-sung, a 2004 South Korean taekwondo gold medalist and former IOC member.

By the time the IOC chose Pyeongchang, most of those agreements had been laid to waste by various North Korean aggressions.

But for Kim and many others, there remains reason to think sport can provide a venue for bringing the Korean family together. In 1991, the two countries fielded a joint team at the world table tennis championships in Chiba City, Japan, an event that retains such a hold on the popular imagination that it inspired the popular 2012 film As One.

"It was a great, positive experience – because, of course, we won," said Hyun Jung-hwa, the South Korean women's double player who, together with North Korean Ri Pun-hui, snatched gold from China. "No one thought we could beat China. But by the North and South coming together, we were able to defeat them," Hyun said. "That made the win even sweeter."

The Gangneung Ice Arena is seen at the Olympic Park in Gangneung, South Korea, Feb. 2, 2018.

Jae C. Hong/Associated Press

She holds similar hopes for the joint women's Olympic hockey team, which will square off against Japan, the two countries' other foremost rival.

"Everyone is really hungry for victory," she said. "I hope the Olympics will be an opportunity for North and South to restart interactions with each other," she added. The women's hockey team "is all about tongil" – reunification.

Think of that team – like the Games themselves – as not merely an athletic pursuit but as a public resource, participating in an Olympics funded by a government with bigger objectives, said Kim Oujoon, a Seoul morning radio host and podcaster who is among the country's top media opinion makers.

"Right now we really need peace on the peninsula, so for that reason the unified team was created," he said. "That team has become a public good."

In fact, he says he's convinced the Games can actually change minds among those hostile to the idea of reunification.

"The Olympics will show a more positive image of North Korea to young people," he said.

Indeed, the potent imagery of the two Koreas marching into a stadium and slapping pucks together may be what leaves the most enduring impression.

"The Olympics are kind of a symbol-making machine," Boykoff, the Olympics researcher, said. "It does appear that North Korea will participate in some fashion. And so if this pivots toward a more peaceful existence between the two countries, well then a lot of people will probably look at the Olympics as the thing that brought Kim Jong-un to the table."

But hopes of Olympic respite have been eroded by renewed tensions. This week, the United States confirmed it will no longer nominate Victor Cha, a respected scholar and former White House official, as its ambassador to South Korea. Cha had pushed back against the idea of a so-called "bloody nose" strike on North Korea. Now his rejection has raised fears that the Trump administration is actively considering a military option. U.S. President Donald Trump did little to quell worry when he warned in his State of the Union address that "North Korea's reckless pursuit of nuclear missiles could very soon threaten our homeland."

Indeed, those missiles – or at least frightening facsimiles of them – are expected to take centre stage next week at a major armed forces parade in Pyong-yang on the eve of the Olympic opening ceremony. Though North Korea has said the parade is "not a military provocation," such a display of firepower threatens to undercut South Korean attempts to foster calm by pausing joint military exercises with the United States, a key North Korean demand.

The suspicion that Pyongyang is using the Olympics to manipulate South Korea has unleashed fury among Moon's opponents on the country's political right – and, in turn, heated new rhetoric from North Korea.

Rather than unify, the Olympics have highlighted divisions both political and social in the South.

"Stop pandering to Pyongyang," thundered an editorial in the JoongAng Ilbo newspaper. The Chosun Ilbo has warned about Kim Jong-un stealing the spotlight and making South Korea into "a propaganda tool for the North Korean regime." The Dong-A Ilbo, another top conservative daily, has pilloried the country's leadership as pushovers standing "helpless in front of North Korea's typical tactic to tame the South with its participation in the Pyeongchang Olympic Games."

North Korean athletes arrive at the the Olympic Village in Gangneung, South Korea.

KIM HONG-JI/REUTERS

On Wednesday, Choson Sinbo, a North Korean mouthpiece in Japan, fired back, warning about the Games tumbling into an "Olympics of confrontation."

Moon's own supporters haven't been much more charitable.

The government-mandated addition of North Korean players onto the Olympic women's hockey team struck painfully close to home for young South Koreans who have spent years preparing for jobs that may never materialize in a country where youth unemployment has hit record highs. For the South Korean players who will have to cede ice time to the new additions, it amounts to "taking away someone's place by outside force," said Kim Sung-yeon, 20, a sports medicine student.

"It feels like the country is saying, 'You always need to be prepared to give up for the nation what you've accomplished and put so many efforts toward,'" added 20-year-old Kim Seo-young, a political science and international relations student.

More than 57,000 people have signed a petition against the unified team.

Moon rode a wave of youth support to office last year. But the feeling of Olympic disenfranchisement has been so strong that his approval rating plunged six points following the formation of the joint hockey team and has continued to decline since. The effort to promote unity had only served to underscore a widening generational gap in a country where young people have little interest in reunification with what they see as a separate country.

"I remember the 1988 Games, how we were united and welcoming the Olympics. I don't see that now," said Kwon Soon-jeong, general manager of the Center for the Research and Analysis of Public Opinion at Realmeter, one of the country's top pollsters.

"Nationally speaking, Koreans are not welcoming the Games."

Tickets have sold slowly. By Thursday, little more than a week before opening day, more than a quarter of all Olympic seats remained unsold (Vancouver and Sochi were almost sold out). Neither NHL players nor local figure-skating sensation Yuna Kim will compete – and ticket sales have been slower than average for both those sports. Skeleton, in which South Korea has gold medal hopes, had sold less than half of its available tickets.

Meanwhile, some of the country's most senior voices on North Korea are warning that the Games may actually provide Pyongyang cover to pursue its nuclear agenda.

The promise of Olympic calm "creates an illusion of peace without actually strengthening peace," said Chun Yung-woo, who was South Korea's top representative at international denuclearization talks a decade ago. He sees strategic calculation in North Korea's friendly new face, as the regime seeks to frustrate international momentum toward harsher sanctions and create a difficult environment for the United States to launch a military strike.

All the while, North Korea "will keep enriching uranium. It will keep building up fissile material and a nuclear arsenal," said Chun, who is now chairman of the Korean Peninsula Future Forum.

He warns against what he calls false Olympic hopes.

"North Korea will keep increasing its capability to destroy peace. So peace will become more fragile, more precarious, after the Olympics than before."

With reporting by Cynthia Yoo

*References:

-Goble and Mail

'평창2018시리즈 ' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 평창2018 제132차 IOC총회개회식 문재인대통령 참석 연설 및 총회개회식이모저모 종합 스케치 (0) | 2018.02.07 |

|---|---|

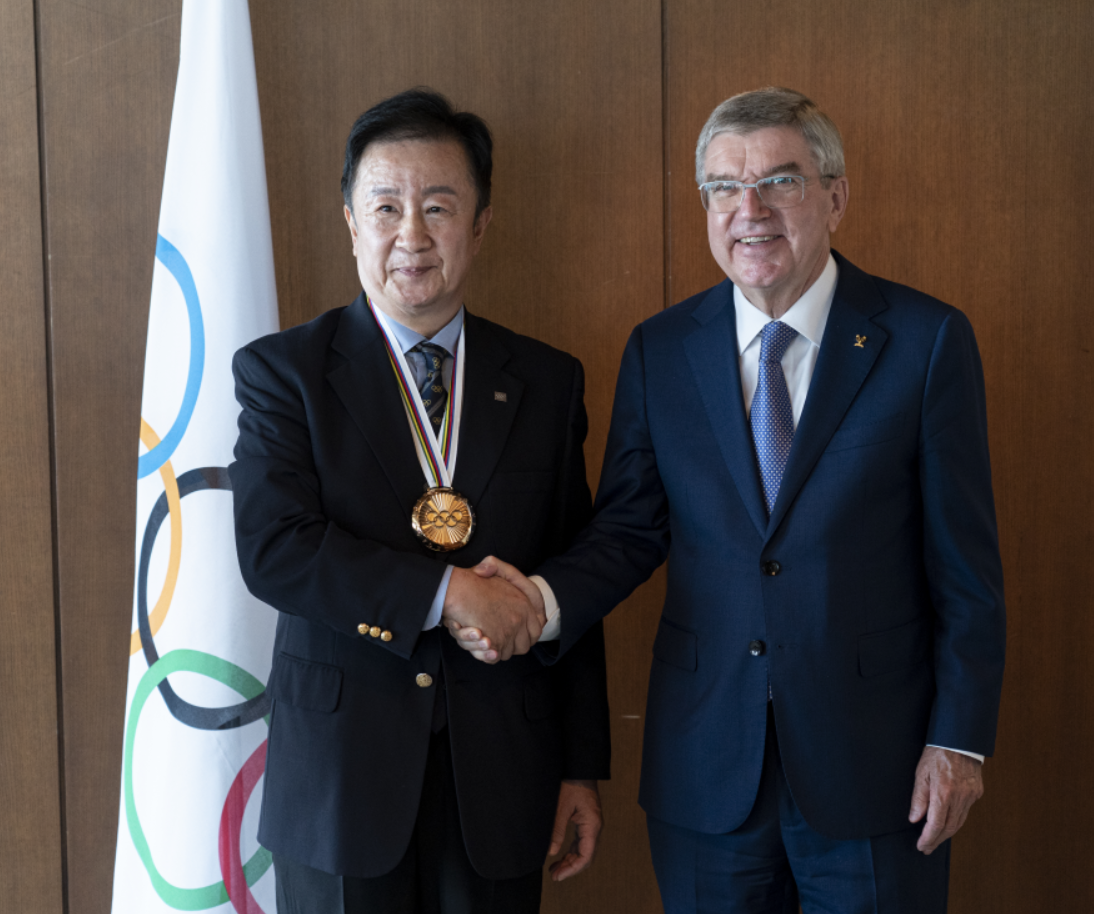

| 평창2018 Bach(IOC위원장)특유의 이희범(POCOG위원장)평가론 삼행시(三行詩)스케치 (0) | 2018.02.06 |

| 평창2018개최 IOC회의 및 주요행사 일람표 요약정리 Update (1) | 2018.01.30 |

| "하나 된 평창의 꿈" 특강 중 평창2018 관련내용 스케치 (0) | 2018.01.26 |

| ‘평화 올림픽’ 평창2018 외교적 기대효과 (0) | 2018.01.24 |